Ofqual is attempting a double-U-turn on how to define grade 9 in the new GCSE scale.

This will affect the highest attaining learners in all our schools, all staff who teach them and all those who rely on GCSE grades to select high-attaining students, including university admissions staff.

It also has implications for the performance of all state-funded schools on government accountability measures, so it is not small beer.

You might be forgiven for missing this, since it was announced in the graveyard slot on Friday 22 April, while most educators’ attention was diverted to the furore over forced academisation.

A brief press release announced a second consultation on setting GCSE grade standards. We had anticipated an exercise focused on the subjects first introduced in 2018.

But Ofqual is also proposing to reverse its previous decision, already once revised, on the definition of grade 9 boundaries (and indeed grade 8 boundaries) for GCSEs in English language, English literature and maths awarded in summer 2017.

This matters considerably for thousands of learners who are already part-way through their KS4 programmes of study.

.

Ofqual’s first position: the 50% rule

In April 2014 Ofqual launched an initial ‘Consultation on setting the grade standards of new GCSEs in England’.

This invited views on whether:

- The G7 grade boundary should be set:

‘…so that, all things being equal (in other words if the ability profile of the cohorts were the same), the same proportion of students who would have been awarded a grade A or above in the last year of the current GCSE is awarded a grade 7 or above in the first year of the new GCSE’

- Alternatively or additionally, the G9 grade boundary should be positioned:

‘…so that half of the percentage of students previously awarded an A* in a subject is awarded a grade 9. This would make the standard of performance required for the award of a grade 9 really exceptional.’

A national reference test was also proposed, to be piloted in 2016 and introduced in 2017, to inform standard-setting in English language and maths from 2018:

‘If, overall, students’ performance in the reference test improves on previous years (or indeed declines) this may provide evidence to support changing the proportion of students in the national cohort achieving higher GCSE grades in that year.’

.

Ofqual’s second position: The 20% rule

An analysis of consultation responses was published in September 2014, together with an Ofqual Board Paper on setting grade standards for GCSEs in 2017.

The accompanying press release summarised the outcomes, which included:

- ‘Broadly the same proportion of students will achieve a grade 7 and above as currently achieve an A and above’ (so as proposed)

- ‘For each examination, the top 20 per cent of those who get grade 7 or above will get a grade 9 – the very highest performers.’ (so a significant change).

The analysis of responses shows that a small majority of respondents thought the original proposal was appropriate (58%) and useful (56%).

Some concern was expressed that ‘setting such a high limit would restrict achievement of some students’. Conversely, there was support for the view that G9:

‘…should test the most able and be restricted to a small number of exceptional candidates. There was a feeling from a small number that grade 9 should be set to be highly aspirational and an indicator of exceptional performance’.

The Ofqual Board paper over-rode the preference of the majority by recommending a different approach to setting the G8/9 boundary which had not been mentioned in the consultation document.

The G7/8 boundary would be determined arithmetically and positioned half way between those on either side of it.

There was a clear expectation that the decisions relating to English language, English literature and maths in 2017 would be applied to those GCSE subjects introduced subsequently (my emphasis):

‘This paper focuses on awards of new GCSEs in summer 2017. The three subjects involved will be awarded again in summer 2018 alongside the first awards of some other GCSE subjects. The Board’s decisions for summer 2017 GCSE awards provide the structural framework for making subsequent awards. We will evaluate the implications further before providing the Board with recommendations for any changes, probably at the level of procedural changes, for summer 2018 awards.’

The change of approach for G9 reflected modelling undertaken alongside the consultation. This tested the original approach, the new approach and a third model involving setting the grade arithmetically.

Conclusions were that:

‘The 50% rule was not generally favoured as it was seen as being tied too closely to present grade A* awards. If there are concerns about the comparability of grade standards of A* across boards or across subjects then it may not be the best starting point for the new system. Setting grade 9 arithmetically received little support. The 20% rule was considered the best option at both meetings…

…Using the preferred model effectively fixes the relationship for the highest grade on the new grading scale as in all subjects, 20% of grade 7, 8 and 9 candidates are always awarded a grade 9. The grade 8 boundary mark is then set arithmetically…’

The Board paper showed how this decision would affect grade distributions across summer 2013 results in 24 subjects.

Under the 50% rule, the percentage of G9s would have been 1.6% in English, 2.8% in English literature and 2.5% in maths. It would reach as high as 16.6% in classical subjects.

Under the 20% rule, the percentages achieving G9 would be significantly higher in English and somewhat higher in maths: 2.8% in English, 4.6% in English literature and 2.9% in maths. But the percentage achieving G9 in classical subjects would fall to 12.0%.

The paper commented:

‘Some subject communities will see the new rule as disadvantaging their subject and perhaps affecting the number of entries. Inevitably adopting a new rule will produce a different pattern of results from those we have now.’

It added:

‘We will return to the Board with further analysis before making a recommendation about whether the 20% rule should be applied in the same way in all subjects given the varying impact it will have.’

But this is rather undercut by the statement earlier that any adjustment would ‘probably’ be ‘at the level of procedural changes’.

.

A problem emerges

As far as I am aware, this issue did not resurface publicly until early 2016.

The first time I spotted it was in a run-of-the-mill speech given by Ofqual’s Director of Strategic Relationships, General Qualifications on 9 February 2016.

He said:

‘At the top of the ability range, the new GCSE grading system will allow us to differentiate more clearly. So for example the top 20% of those who get grade 7 or above will get a grade 9 in each exam in English and maths in 2017. But we have not yet decided our approach to awarding GCSE subjects beyond 2017. We think that for grades of 7 and below, the approach that has been taken for the first awards in 2017 is likely to be most appropriate.

However, unlike English and mathematics, which are taken by the national cohort, the awarding of the top grade 9 in other subjects, particularly those with smaller cohorts, is somewhat more complicated. In particular, using the approach in which the top 20% of grade 7 candidates gets a grade 9 could introduce disadvantages in some subjects. We have looked carefully at a range of alternatives, and hope to launch a consultation on these in March.’

I tweeted

.

.

For the implication behind this statement was apparently that, for GCSEs awarded for the first time in 2018, G9 could be derived differently than it had been for English and maths.

This would have implications for standard-setting in future years, meaning that it would either be easier or more difficult to secure G9 in those three GCSEs than in any others. Given issues of inter-subject comparability I couldn’t understand how that could be acceptable.

March came and went and there was no consultation.

Then on 21 April Cambridge Assessment published a paper ‘A possible formula to determine the percentage of candidates who should receive the new GCSE grade 9 in each subject’.

It notes the importance of comparability in the context of the Attainment 8 and Progress 8 accountability measures.

It argues that:

- Subject cohorts achieving a high proportion of top grades are likely to have relatively higher ability (by which it probably means relatively higher prior attainment) and so a greater propensity to achieve G9.

- So awarding G9 to a flat percentage of those at G7 in each subject does not maintain comparability.

- An alternative formula – a flat rate 7% plus half of those awarded G7 or above – would be more equitable. So, for example, if 40% of a cohort is at G7 or above, G9 would be awarded to 27% of them (7% + 20%) but if 80% are at G7 or above, G9 would be awarded to 47% (7% + 40%).

- This would mean that, across all subjects, the overall percentage achieving G9 would be close to 20%. Moreover in ‘almost every subject’ the percentage achieving G9 would be lower than the percentage who achieved an A* grade.

.

.

Ofqual’s second consultation document appeared the following day.

.

Ofqual’s third position: 7% plus half

Ofqual’s Friday press release announced:

‘In September 2014 we announced our decisions about the awarding of new GCSEs in English language, English literature and mathematics which will be first awarded in summer 2017.

We are now consulting on the approach to be taken in all other subjects from 2018 and on a modification to our previous decisions for English language, English literature and mathematics about how grades 8 and 9 are set…

… We are proposing to adopt a modified approach to the award of grades 8 and 9 across all subjects, including English language, English literature and mathematics. We would not normally suggest adapting a previously announced decision but we believe it is the fairest outcome for students.’

The new consultation document ‘Setting the grade standards of new GCSEs in England – part 2’ is accompanied by a research paper commissioned from Education Datalab on options for setting the G9 boundary. It also references the Cambridge Assessment paper.

Responses are invited by Friday 17 June, some six weeks hence at the time of writing.

The document proposes the equation for deriving G9 recommended in the Cambridge Assessment paper, with G8 continuing to be ‘equally spaced in terms of marks from the grade 7 and 9 boundaries’.

The change tot the grade boundary for G9 would have a consequential effect on the boundary for G8.

.

.

The formula would be used only for the first year in which new GCSEs are awarded, so in 2017 for English language, English literature and maths and in 2018 or 2019 for other subjects.

Thereafter the grade standard would be carried forward:

‘However, we will also look to improve on the current approach where possible, for example through using the outcomes from the National Reference Tests.’

This is not quite as bullish as previous statements about the value of the reference tests. Later on in the document there is an additional note of caution:

‘The NRT are new and the extent to which they may be relied upon in future awards and across subjects is yet to be determined.’

The consultation paper runs briefly through the convoluted history above – the ‘50% approach’ discarded in favour of the ‘20% approach’ – also mentioning two alternative methods for deriving G9 that Ofqual has already set aside:

- Judgemental awarding, in which a generic description of G9 performance would be applied across all subjects, supported by subject-specific exemplification.

- Extrapolation, in which grade widths below G7 would be applied to G8 and G9.

.

The nub of the problem

Then there is the admission of the problem that Ofqual and its advisers should have foreseen back in 2014:

‘Our original proposal to use the 20 per cent approach for the award of grade 9 was for English language, English literature and mathematics. These are subjects taken by a very large proportion of the cohort. However, using the same approach in other subjects does create problems. It compresses the range of top grades awarded across all subjects, regardless of different entry profiles and the proportion of top grades awarded in pre-reform qualifications. The 20 per cent approach reduces the proportion of students awarded top grades in subjects where proportionally more students will achieve a grade 7 or above, and increases the proportion of students awarded top grades in subjects where proportionally fewer students achieve a grade 7 or above – this was not our aim. Implementing the 20 per cent approach in all subjects could affect entry patterns in an unintended way.

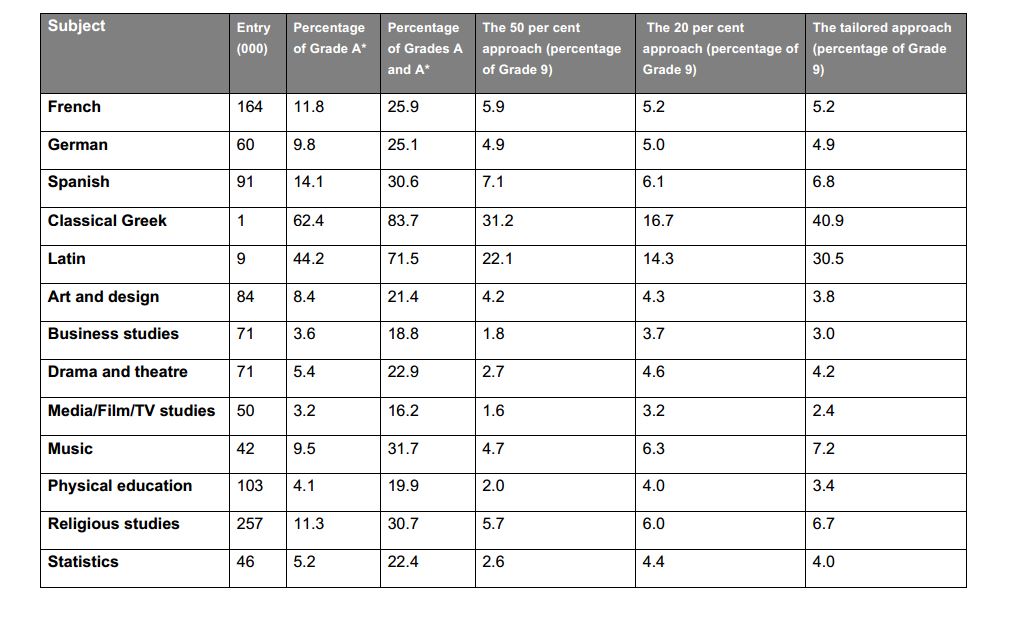

The greatest impact of the 20 per cent approach would be on students studying biology, chemistry, physics, classical Greek, Latin and some languages that are less commonly taught in schools. For chemistry the proportion of pupils achieving the top grade would drop from 19.6 per cent to 9.3 per cent. In Latin the proportion of pupils awarded grade 9 would be substantially lower than the current A* percentage (14.3 per cent compared to 44.2 per cent). For both of these subjects it would become significantly more difficult to achieve the top grade.

In order not to make it much harder to achieve the top grade in some subjects than in others compared to the present position, we do not consider that we should award grade 9 to a flat percentage of those achieving at least grade 7 across all subjects, and we have sought an approach that does reflect the different grade proportions currently seen in different subjects.’

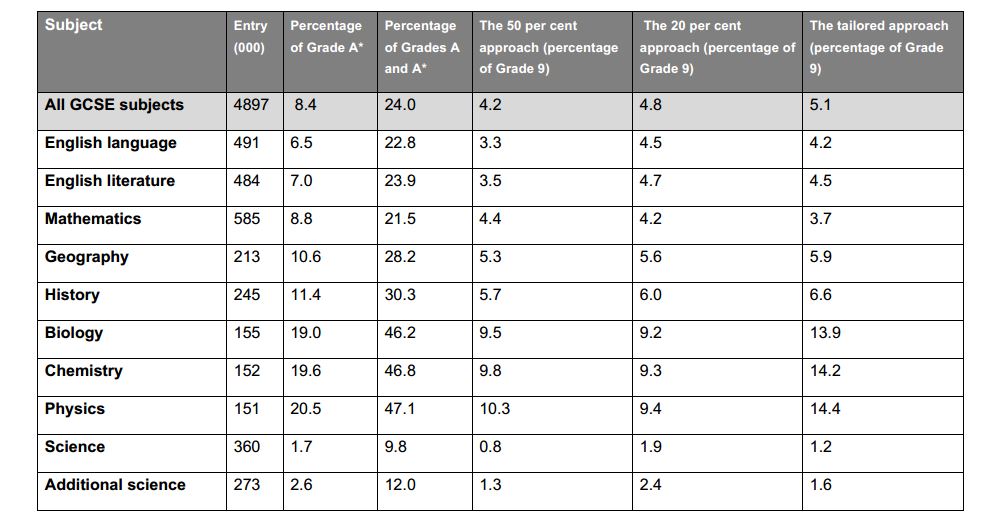

The consultation paper reproduces a table, a simplified version of one in the parallel Education Datalab report, showing the comparative impact of its three different preferred approaches alongside A*/A grades (2014 results) for selected subjects.

.

.

Some of these results do not agree with those set out in the earlier Ofqual board paper, quoted above. It seems unlikely that all the variance is attributable to differences between 2013 and 2014 GCSE results.

According to these figures, the national impact of the proposed change on this set of results would be to reduce the number of G9 passes by just under 1,000 in English literature, by almost 1,500 in English language and by close to 3,000 in maths.

These are figures for both independent and state-funded schools. We do not have data for the state-funded sector, nor any modelling that predicts the impact of reformed GCSEs on the grade distribution.

The consultation document argues that the only GCSEs in whch more 9s than A*s would be awarded are English (as opposed to English language) and science, both of which will be discontinued.

It says that the preferred option will be much less likely than the ‘20% approach’ to:

‘…encourage subject choices to be influenced by the perceived ease of achieving a top grade’.

Additionally it suggests that the impact of this change on the 2017 examinations will be small, with only slightly fewer G9s being awarded – about 8 in each subject across a year group of 200 compared with 9 per subject under the former ‘20% approach’.

This gives the incorrect impression that the impact of this decision is marginal. The effect on G8 is not quantified.

This strategy of downplaying the impact of the change is continued in a statement suggesting that the impact on accountability arrangements ‘would be negligible’. But surely its prime purpose is to ensure comparability between GCSE scores included in the Attainment 8 and Progress 8 measures?

Finally the paper arrives at the rather awkward statement:

‘There appears to be no clear rationale for us to adopt a different approach to the award of grades 8 and 9 in these subjects. Although they are important for a number of reasons, including progression, it does not follow that a different approach should be applied to English language, English literature and mathematics.

If awards had already been made for new GCSEs in English language, English literature or mathematics, and we then changed the approach, there would be inconsistency in grade 9 standards between years. However, as the first awards are over a year away, no inconsistencies would be created by modifying the approach to awarding grade 9 in these subjects now.’

Roughly translated, this means ‘we can’t find a reason to justify sticking with our first revised decision, so we need to revise it again. It’s not quite as serious a cock-up as if we’d turned a blind eye.’

Consultees are asked separately ‘to what extent they agree or disagree’ with these proposals as they apply to 2017 and 2018 examinations respectively. Quite what would happen if a different view is expressed on each head is left a matter for conjecture.

.

Education Datalab’s Report

Datalab’s analysis is based on summer 2014 GCSE results for candidates from state-funded and independent schools. This might suggest that it was conducted some time ago, although the text says the 2015 results could not be used in the analysis because of the ‘SATs strikes’ that year. I am not entirely convinced.

It covers ’72 subject mappings with at least 1,000 entrants’ including IGCSEs excluded from the 2014 performance tables, but not double award and vocational GCSEs.

The awarding of grades on the new scale is modelled through a statistically complex proxy based on the total points scored by pupils in their best six GCSE entries excluding community languages. I am not qualified to judge how reliable it is, but there are no obvious health warnings.

Datalab’s more detailed table points out that, contrary to the statement in the consultation document, the new approach would generate more G9s than A*s in both Portuguese and environmental science.

The report adds that:

- In terms of the overall percentage of G9s awarded, independent and state grammar schools benefit most from this new ‘tailored rule’. This impact is not so significant within major subject groupings however.

- In some subjects, but not others, the new approach gives a steeper gradient in the proportion of G9s awarded by ‘ever 6 FSM’ decile of a school. Conversely the tailored approach is slightly more favourable to pupils eligible for the deprivation element of the pupil premium. (Some 1.3% is likely to be awarded a G9 compared with 4.5% of not FSM6 pupils. The comparable figures for the previous option are 1.2% and 4.3% respectively. )

- Subject to more statistical proxies to determine the incidence of G8, the change to the new 1-9 scale ‘will widen the gaps between the schools with the most able intakes and the rest’ in respect of both Attainment 8 and Progress 8, but this will not be materially affected by the shift to the ‘tailored rule’.

Some of these points are reproduced in the consultation document, but perhaps not as carefully as they might have been.

.

Verdict

I accept the argument that version 3 of grade 9 is preferable to either of its predecessors, but it too has imperfections.

Given the convoluted process involved in arriving at version 3, there must be some reason to question whether Ofqual has arrived at the optimal solution.

It is disturbing that Ofqual is recommending its third preferred approach within two years. There has been no explanation of why it could not get this issue ‘right first time’.

It is equally disturbing that Ofqual has taken close on 20 months to realise it had this problem, to admit the problem and to propose a solution. This hints at a conspicuous gap in the project planning for the introduction of the new GCSEs.

I appreciate that, this time round, it had no option but to complete the modelling before launching the consultation, but I’m sure that all stakeholders, schools especially, would have preferred to have known sooner that the problem existed, even if some temporary uncertainty ensued.

For no-one needs reminding that the DfE workload protocol says:

‘Significant changes to qualifications, accountability or the curriculum should avoid having an impact on pupils in the middle of a course resulting in a qualification (i.e. pupils should start a course knowing that the content or assessment criteria will not change during the course).’

Since I wrote this post I’ve seen another – on the Just Maths blog – expressing concern at this example of ‘moving goalposts’ and the uncertainty this creates for teachers and students alike.

I don’t underestimate the difficulties involved in resolving such complex issues, and apportioning blame is a waste of valuable time and energy.

But, at a time when the government is rightly refocusing on the needs of high attainers, having admitted in the white paper that the most academically able are a ‘neglected group’, this rather unhelpfully suggests a continuation of the problem.

.

TD

May 2016

Reblogged this on Gifted Phoenix.

LikeLike